The Birth of "Midnight Rider"

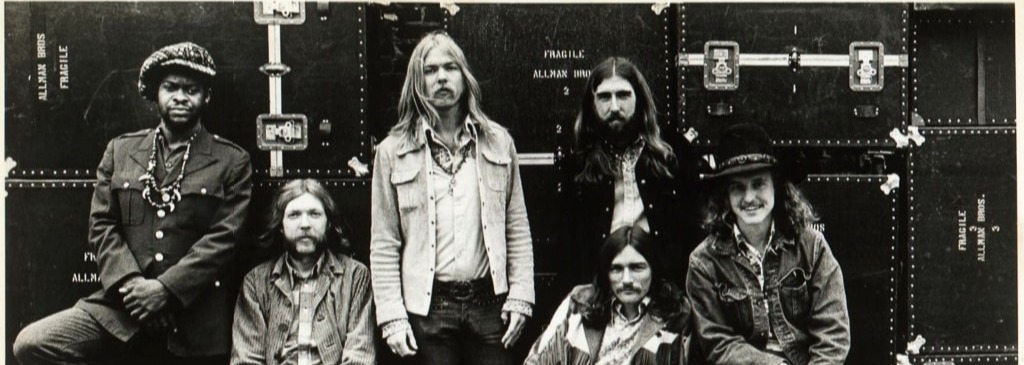

Author's Note: If you're from Macon, Georgia, it's practically a requirement that you love the Allman Brothers Band. We celebrate every place they lived, even if it's no longer standing; we have a marker for places where significant things in their history here happened; and we lift them up in Glory annually with a festival. We even pay sweet homage at their resting places. We are forever thankful for the legacy of music they gave our town and the world.

My favorite song by them has always been "Midnight Rider." I love the catchy guitar riff and the tale of someone edgy and restless. When I heard the story of how the song came to be, I loved it more and knew I had to write about it.

If you come to Macon, please visit our many Allman Brothers Band treasures, including The Big House Museum, Capricorn Studios (now owned by Mercer University), and pay your respects at Rose Hill Cemetery.

Some songs feel lived before they're written. Gregg Allman's "Midnight Rider" is one of those—part blues confession, part Southern folk tale, and part outlaw hymn. Its origin story is just as restless as the song itself, stretching from the quiet banks of Lake Juliette to a late-night break-in at Macon's Capricorn Studios.

In 1970, Gregg Allman often retreated to Lake Juliette, a spot outside Macon, Georgia, where he found peace away from the whirlwind of touring with The Allman Brothers Band. One evening, guitar in hand, he sat by the lake with only a candle for light. Surrounded by woods and still water, he began shaping a song that spoke to the way he and his bandmates were living—always moving, never settled, trying to stay one step ahead of both fame and their own struggles.

"The words just came out," Gregg later recalled in My Cross to Bear. "I wrote the whole damn thing in one sitting. It was like somebody handed me that song."

Lines like "I got to run to keep from hiding, and I'm bound to keep on riding" weren't just lyrics; they were reflections of a life constantly on the move, balancing ambition with a sense of chasing something just out of reach.

Still buzzing with inspiration, Gregg and roadie Kim Payne drove back to Macon, determined to capture the song before it slipped away. They headed for Capricorn Sound Studios, the band's home base. But it was after hours, and when they called Phil Walden, the Allmans' manager and co-founder of Capricorn Records, Walden shut them down. "Phil wouldn't open the door," Gregg remembered. "Said it had to wait until morning."

But Gregg wasn't about to let "Midnight Rider" wait. With Payne's help, he pried open a window and slipped inside. "I had to get it down before it left me," he said. By candlelight—just as it was born at Lake Juliette—he recorded a demo. Voice and guitar, nothing fancy, but enough to lock the spirit of the song onto tape.

As Gregg worked the lyrics, Payne listened closely. At one point, he offered a suggestion: "I've gone past the point of caring." Gregg loved it. "Kim threw that line in there," he later admitted. "And it fit perfect. Sometimes the best things just come like that."

That offhand contribution became part of the finished song, proving that even a roadie hanging around the studio could help etch rock' n' roll history.

The next day, Duane Allman and the rest of the band heard Gregg's rough demo. They built the song around it: Duane's aching slide guitar, Berry Oakley's hypnotic bassline, and percussion that gave the track its earthy, rolling momentum. Producer Tom Dowd kept it lean, letting the space and mood breathe.

Gregg later said, "That was one of the songs I was proudest of. It said exactly what I was feeling, and the band made it soar."

What started as a midnight demo in a candlelit studio didn't stop there. "Midnight Rider" became one of the Allman Brothers' most iconic tracks, but it also took on a life of its own. Gregg re-recorded it for his 1973 solo album Laid Back, slowing it down into a soulful lament. Willie Nelson turned it into a country hit in 1980, and Joe Cocker's gravelly version gave it a blues-rock punch. Each new take carried the spirit forward.

"People do that song and they make it theirs," Gregg once said. "But I'll always remember it the way it started—me and Kim, breaking into the studio, with one candle burning."

That night—Phil Walden saying no, Gregg climbing through a window anyway, a roadie tossing in a key line—has become Southern rock folklore. It wasn't polished, but it was honest. "Midnight Rider" distilled the essence of who Gregg was at that moment: a musician living on the edge, chasing freedom, haunted but unbroken.

Half a century later, the song still feels alive every time it plays. You can almost picture Gregg at Lake Juliette, scribbling lines by candlelight, sneaking into Capricorn Studios, and nodding as a roadie's offhand phrase helped lock the song into place. Midnight Rider wasn't just written—it was lived.

Post a comment